The building was originally designed by John Burnet, the father of Sir John James Burnet in 1871. This was for the part of the building containing the swimming pool, the Senior and Junior baths and the Senior and Junior changing rooms which now forms the northern part of the building.

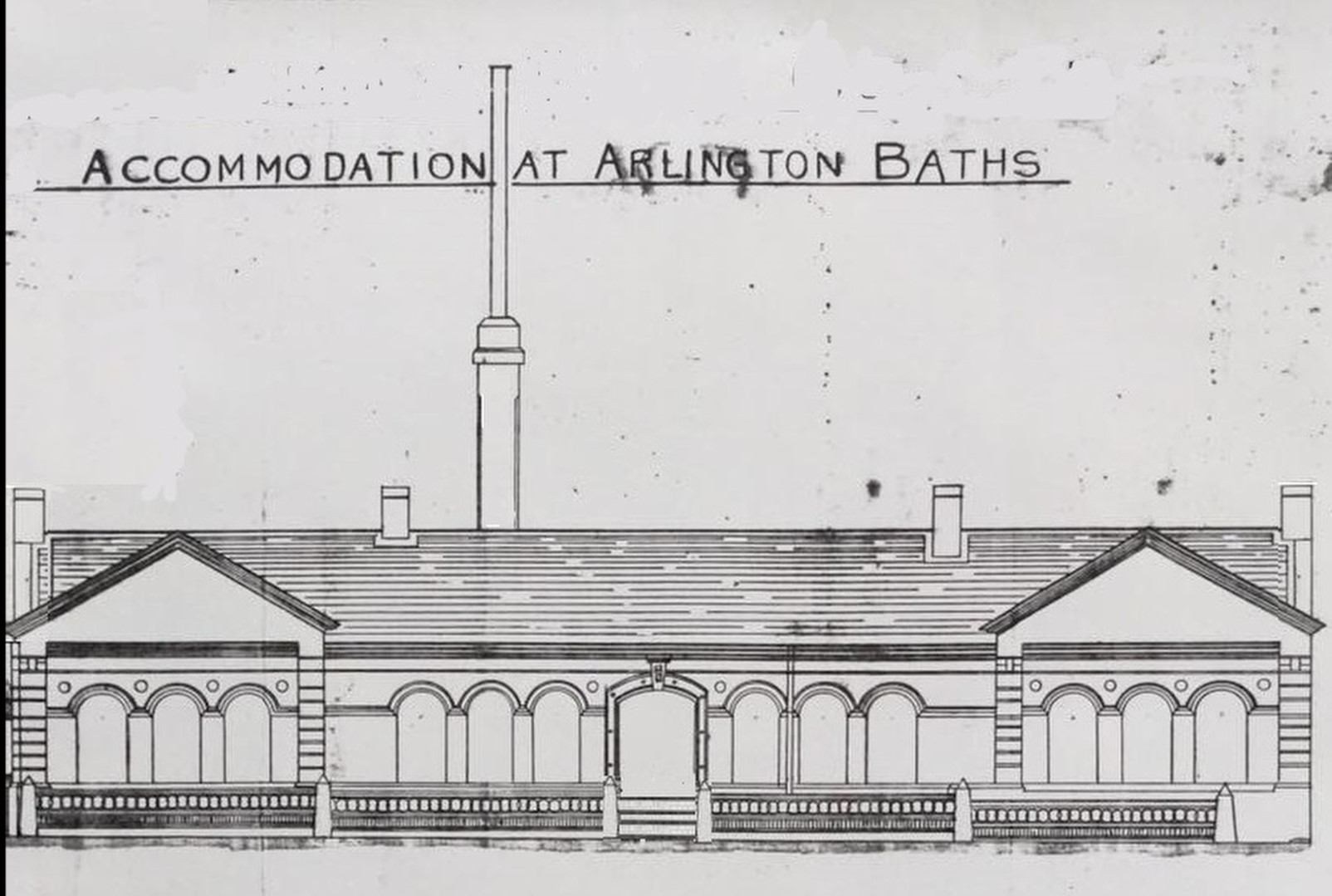

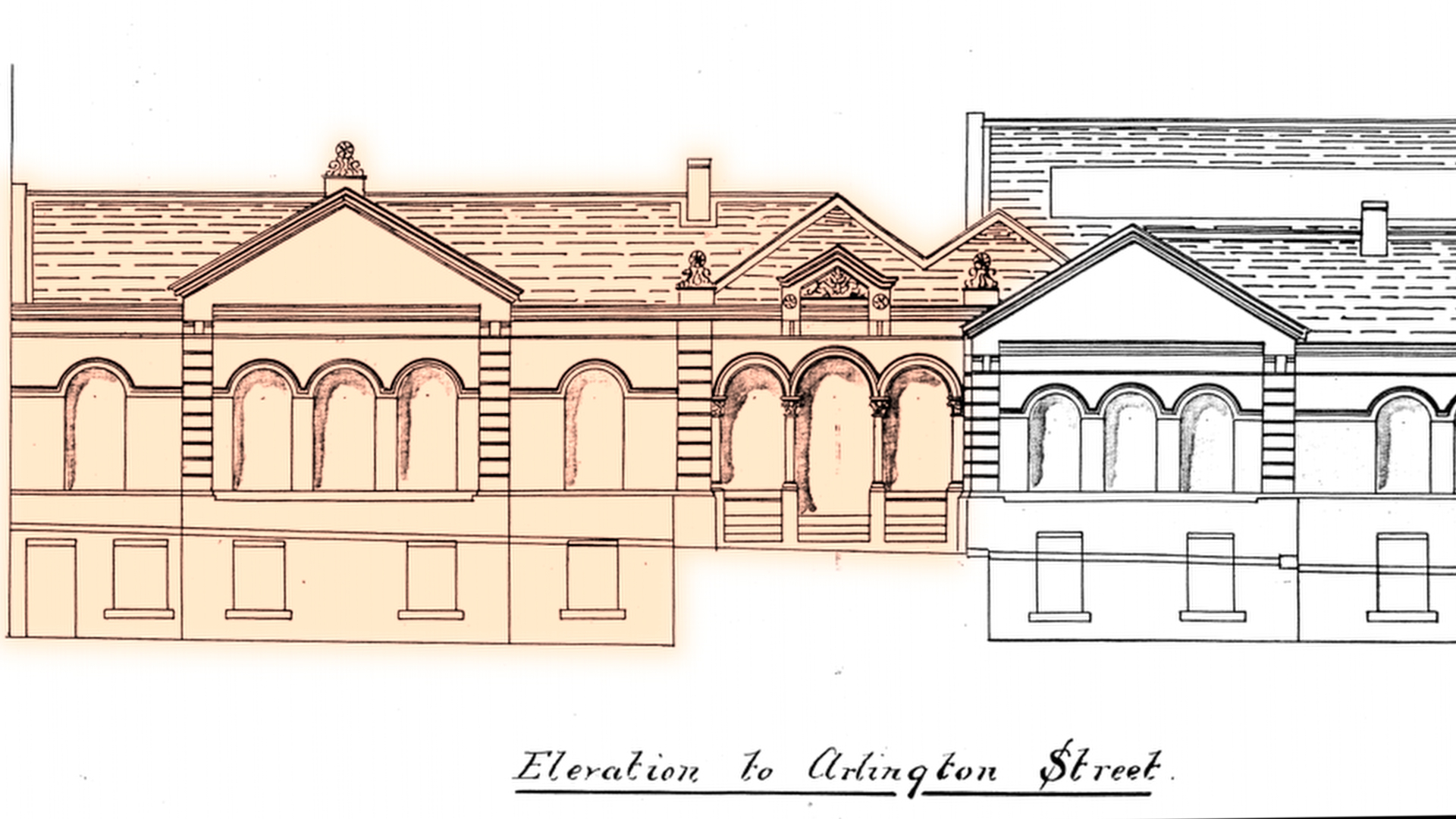

As originally designed by Burnet the building was single storey and conceived as a kind of theme and variation on the idea of subdivision by twos and threes. Thus the main facade onto Arlington Street was modulated by means of two pavilions, located at either end of the building with the centre marked by arched windows arranged in groups of threes. The effect is that of a restrained and modest Classicism, more rural than urban in its nature, well proportioned and pleasing in an unpretentious way.

To describe the design as Palladian would perhaps be to stretch a point too far – although Palladio did draw his influence from Roman Farm buildings. Nonetheless Italianate influence is obvious not only in the balance of the elements but also in the use of a “piano nobile” by which the main spaces are built on top of a semi basement level containing smaller spaces servicing the larger accommodation above. One entered the building at the higher level through the arched entrance in the middle of the facade, coming straight out onto the transverse axis of the pool. From this point the emphasis of the building swung through ninety degrees onto the main axis of the pool hall along which the other accommodation was laid out. The hall itself reinforces the symmetry of the building by its imposing rhythm of exposed wooden roof trusses supporting a simple pitched roof lit by strips of glazing.

Burnet’s intention was therefore to create a composition organised symmetrically, that is by halves, but relieved by a sub-division by threes. The counterpoint between the rhythm of twos played off against the rhythm of threes gives the building its richness.

Also well worth mentioning was the plenum system used to heat the building. Whether by accident or design, this system, in which heated air is passed through the building by convection via ducts built into the fabric, owes its origins to the Roman hypocaust. It was an excellent system, ideal for use in the saturated atmospheres of swimming pools because it encouraged ventilation. It created much comment at the time and featured in contemporary textbooks.

See more about the life of John Burnet and his other works in the Glasgow University story and on the Dictionary of Scottish Architects .

Not long after the building was opened, in fact barely before Burnet had time to vacate the site, a Turkish Suite plus ancillary accommodation was added in 1875 by Charles Drake, utilising his pioneering poured concrete construction technique, allowing the membership to increase to six hundred. The Turkish Suite – which lies at the back of the plan and to the south west of the original building, is justly well known. A Glaswegian homage to the Alhambra, consisting of a large square room, heated to high temperatures by plenum with tiled walls and floor and a ogival shaped roof studded with small star shaped windows glazed with coloured glass, sufficient only to light the space dimly. There is also a fountain in the centre. In an atmosphere of sepulchral calm the bathers recline on benches along the walls sweltering in superheated seclusion. No talking is allowed within the space. The remainder of the Turkish Suite consists of a hot room, cool room, shampooing room and washing room. Originally the washing room connected to the pool via a swim through. In front of the Turkish Suite, a reading room (now the members lounge), shoe hall and entrance hall were added using more traditional building methods. The architect did a workmanlike, and it has to be said, sensible job, in simply copying the details of the original building in terms of window groupings onto his extension; nonetheless, a change in eaves level marked it as a separate construction to the south end of the existing building in the form of a single storey "piano nobile" with service spaces below, it extended the facade of the building southwards across the front of the Turkish suite and created the current grand entrance.

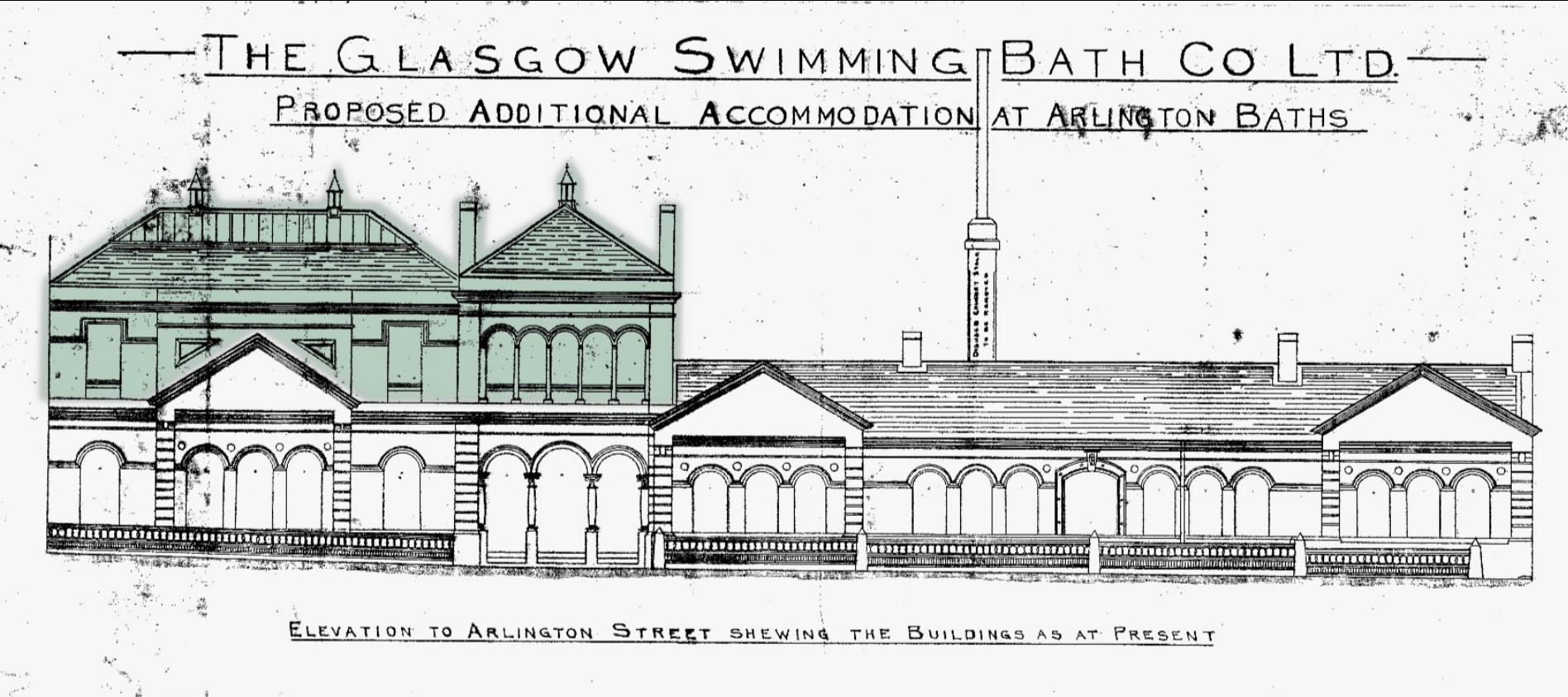

By 1893 more space was again needed. Andrew Myles was employed as architect (Burnet was 79 by this time) to add billiard and card rooms. This extension added another storey accessed by a grand staircase, which in turn led to a junior billiard room (now the reading room), senior billiard room, card room and other administrative spaces, on the first floor. Myles extended the façade up to form an elegant space with exposed roof trusses and glazing at the apex and added a five windowed loggia above the entrance.

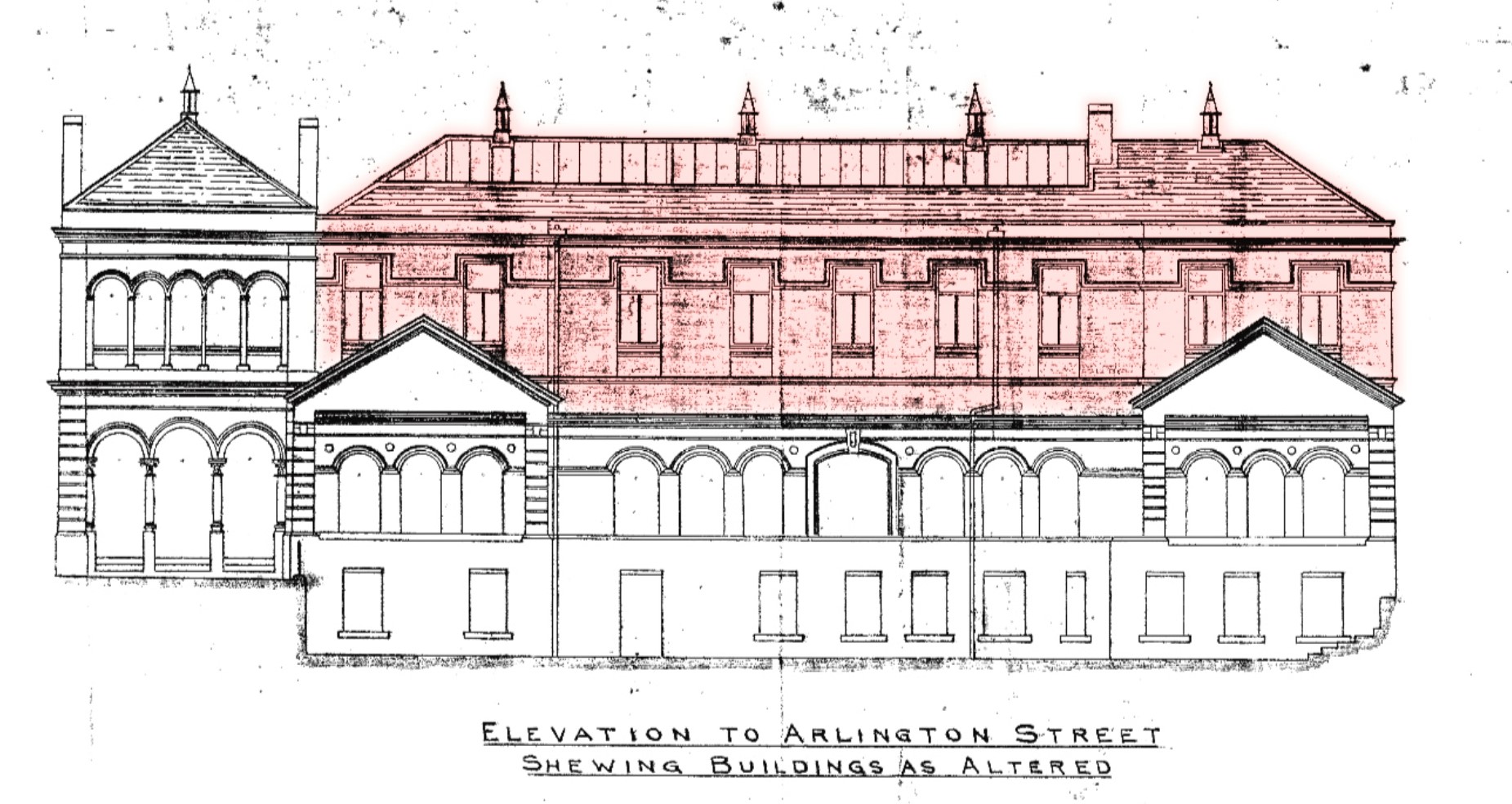

By now, Burnet's simple single storey building must have looked strangely out of sorts, with a two-storey extension attached to the end of it. In 1902 a further increase in membership convinced the Club that a further extension was necessary. Thus order was restored, in some form at least, by the addition of a storey to the street frontage of Burnet's original building. This did not extend the pool hall itself, but simply the bank of rooms which lay between the pool hall and the street. For this purpose the Club engaged architect number four, by the name of Benjamin Conner, who extended the front wall of the original building directly upwards to create a new larger billiard hall and dressing room, now used as a gym – lit by a regular rhythm of single windows. Again exposed timber roof trusses and partial roof glazing are used to good effect in these spaces

In this way, over four phases and a period of thirty years, the Arlington Baths Club grew by a process of accretion. The result, perhaps surprisingly, is not unpleasant. In fact its haphazard eclecticism gives it a strangely modern, or, rather, post modern, appeal. All four phases speak with their own voices, but the result is more of a conversation than an argument. Burnet’s original building can still be seen and appreciated; its companions – with the exception of the entrance bay – do treat it with the deference it is due. The subsequent architects did generally take sufficient notice of what was already there to ensure continuity in what followed this is particularly true of the combination of simple well proportioned spaces, exposed roof trusses and excellent levels of daylighting which are something of a standard throughout the building.

“Arlington Baths Club is an outstanding and early example of an early private members swimming baths, with Turkish Baths and other facilities, for it survives largely as it was built in the late 19th and early 20th century. It has a good interior and was designed by one of the leading architects of the period”

Historic Environment Scotland

"No example, that I am aware of, exists in Scotland of the best form of concrete roof, the domed concrete roof of the Arlington-street Swimming Baths, Glasgow, being the best of the concrete roofs I have executed in Scotland."

Charles Drake